The world of endurance sports presents its unique challenges when it comes to integrating strength training into an athlete’s routine, and many coaches are exploring the possibilities.

As a former pro triathlete turned strength coach, I aim to serve as your guide, offering ideas and insights that can benefit a wide range of coaches and athletes. I don’t believe in a one-size-fits-all approach; instead, I’ll help you explore the complexities of strength training in the context of endurance sports.

Endurance sports demand a lot from athletes, both in terms of cardiovascular endurance and musculoskeletal strength. The question we’re here to explore is how to strategically apply a strength “intervention” to enhance an athlete’s work capacity. It’s not just about building muscle; it’s about equipping athletes to maintain their newfound capacity as they embark on their demanding seasons.

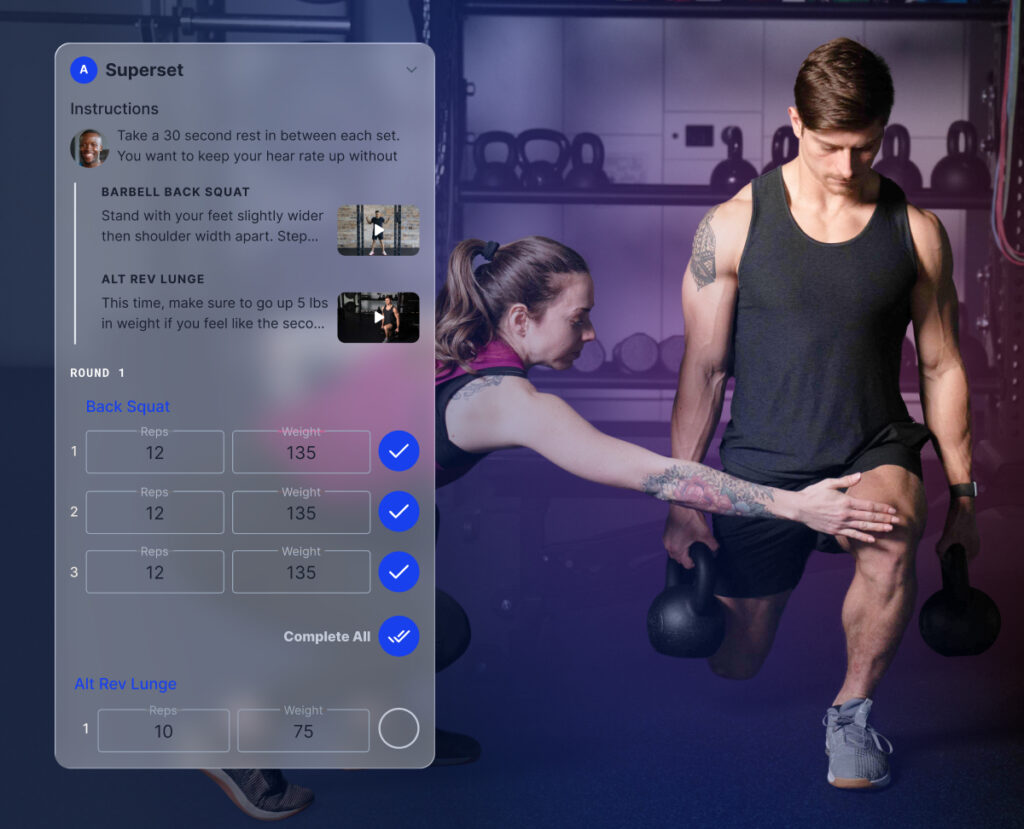

In this post, I explain the basics of programming, how to conduct a movement assessment, the phases of periodization, and how strength training can be assigned in an endurance season. I’ll also provide a sample week for each phase of the season so you can get an idea of how to structure each session using the TrainingPeaks Structured Strength Builder.

Programming Basics: Types of Muscle Contractions, Timing, and Warm-Ups

Before you begin planning a program for your athlete, it’s important to understand the different types of muscle contractions and how you can use each one to maximize your athlete’s individual needs.

The 3 Types of Muscle Contractions

Isometrics are static contractions of the muscle, often done by holding a certain position (think planks). Isometrics are key for tendon health and passive energy storage (aka, the ability of the tendons to store energy). They’re also a great way to load tissue and tendons without inducing muscular damage.

Eccentric contractions occur when a muscle lengthens under load (like the lowering of a bicep curl). These moves are key for absorbing force and increasing the range of motion of stiff tissue. Eccentrics can also decrease stiffness and realign scar tissue. They’re also an excellent tool for overcoming strength deficits or training a new range of motion for a particular movement. Eccentrics can have a muscle “overloading” effect, though. Therefore it’s not ideal to use them during high-volume or high-intensity training. They’re best used during the offseason.

Concentric exercises are the most common form of contraction. This is where the muscle is shortening and generating force. Concentric exercises are the basic building blocks of strength training. Endurance athletes should rarely go under three reps for max strength or over 15 repetitions for hypertrophy/muscular endurance. Most traditional strength exercises have a concentric focus with a slight eccentric component.

The Value of Plyometrics

Plyometrics are key for increasing tendon elasticity. Isometrics are great for stiffness, but without elasticity, injury risk increases. Once plyometrics are trained for six weeks or more, they accrue less muscular damage than both concentric and eccentric lifts. This makes them a great way to maintain strength and coordination without incurring muscular damage during later parts of the season.

Like all exercises, plyometrics should be scaled to the demand of sport. For example, runners need to progress to higher ground reaction force exercises than cyclists.

Timing Strength Sessions With Endurance Workouts

Ideally, strength sessions are completed on key workout days after the endurance workout has been completed unless there are more than two key workouts on that day (such as a double threshold day). In this scenario, it’s best to do the strength session on a recovery/easy day. Some studies show that lifting beforehand might offer post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE), but I would only recommend this to very experienced athletes under supervision.

The goal of any training session is to achieve an adaptation to the specific stimulus. It’s best to rest a minimum of six hours between endurance workouts and strength sessions to allow for optimal adaptations that maximize the effectiveness of your training. I also recommend resting a minimum of one day between sessions to allow the body time to recover. Two days in between is ideal.

The minimal effective dose for strength training is two sessions per week. If you’re working with an experienced athlete, doing up to three or four sessions a week may be effective, but it comes at a high energy cost that many endurance athletes often can’t afford. Less than two sessions a week, and the effects of strength training are far less.

Don’t Skip the Warm-Up

Warm-ups are just as important for strength workouts as they are for endurance workouts. I recommend a mix of the following movements since they target areas that are generally tight and overused in endurance athletes. These movements also require coordination and mobility through multiple planes of motion.

Choose three exercises (the movement assessment mentioned later will help determine what exercises are best for each athlete) and perform ten on each side:

- Downward dog lunge to rotation

- Turkish get-ups

- 90/90 to lunge

- Lateral lunges

- Reverse Nordics

- Curtsy lunges

- Deadbugs

- Birddogs

- Banded ankle mobility

- Adductor mobility

How to Conduct a Movement Assessment

Movement assessments are key for identifying performance bottlenecks and possible issues that can become injuries. Remember that your athlete’s nature of work is really important as well. Questions to consider include:

- How many hours do you spend on your feet?

- Does your job involve extremely early or late hours?

- Does your job require extended hours, 10+ hours straight?

- Is your job physically demanding by nature?

Here are some movements I like to employ during a movement assessment for endurance athletes. These will give you insight into how your athlete is moving and what exercises to use in your programming.

For Evaluating General Movement:

Because this movement requires a decent range of motion and recruits many large muscle groups, it’s great for gaining a general understanding of how an athlete moves.

Aim for 20 total. You’re looking for when your athlete fatigues.

This one gives a good sense of how well your athlete can control ambulation.

Single-leg, Eyes Closed Balance Test

Great way to test proprioception.

For Revealing Imbalances:

Fifteen per side is a good number to shoot for. Look for differences in fatigue between right and left.

Shoot for 20 per side. Again, you’re looking for differences in fatigue between right and left.

Do ten per side. The goal with this one is to see the difference in plyometric ability between right and left.

For Assessing Mobility:

This one tests tightness in the hip flexors, which are often tight on endurance athletes.

This test helps you gauge the tightness of your athlete’s calf muscle and Achilles tendon. Restricted ankle dorsiflexion affects several functional movements, like squatting and landing on one foot.

The Brettzel tests your athlete’s thoracic mobility. Thoracic mobility plays a big role in posture and the ability to breathe fully.

If your athlete is remote, you can record their movements and ask them to send in video recordings. The videos should display full body views, including front, back, and side views.

Strength Training Periodization: A Full Season Overview

An athlete’s strength program needs to complement the current phase of their season, not take away from it. After all, the goal is to help the athlete PR on the course, track, or trail, not on their one-rep max squat.

Here is how I like to program strength throughout the season, starting with a solid base-building phase that allows the athlete to peak at the right time. Click the buttons below to download these workouts to your own workout library. Make sure to use the TrainingPeaks Structured Strength Builder to program your athletes’ workouts, save them to your workout library for future use, and offer your athletes an intuitive front-end experience.

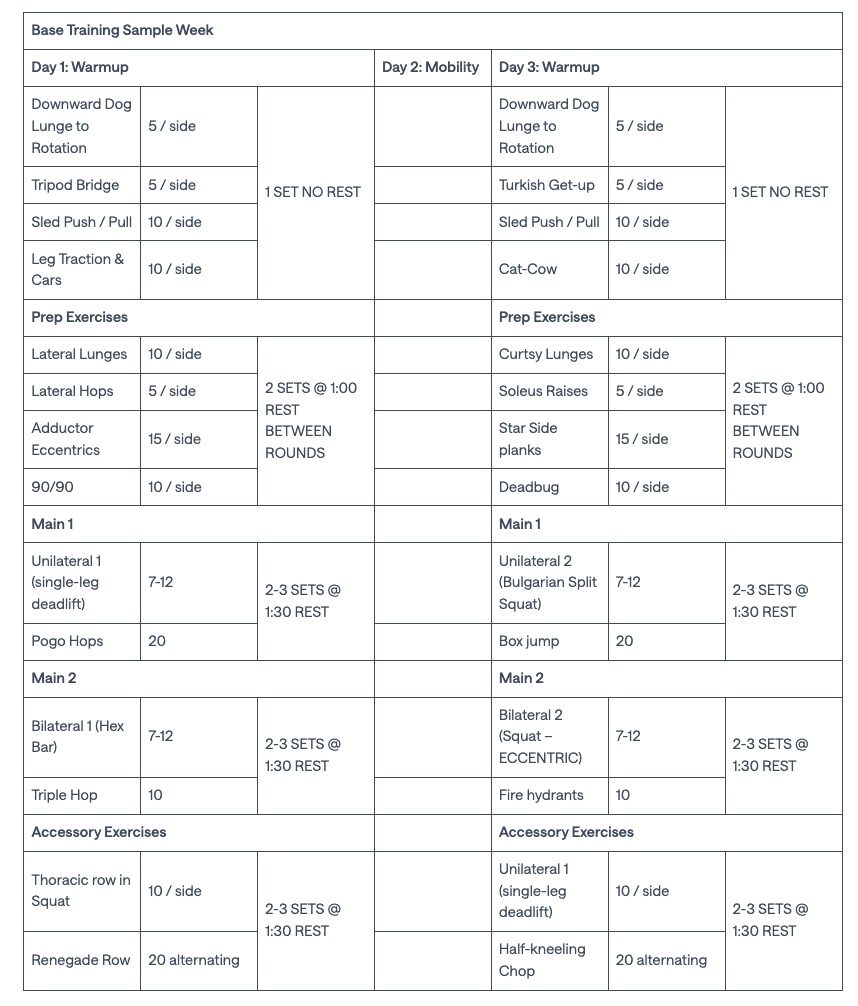

Base Training (8 Weeks)

Base training (aka, the offseason) typically lasts about eight weeks (most research shows an eight-week adaptation phase). You can get a little more aggressive without worrying too much about fatigue since there aren’t any races on the calendar.

Bridging the gap on any key issues and weaknesses is the main goal during this period. If there is a big deficit in strength, you can make a major physiological change here. Basic principles of hypertrophy can be paired with plyometrics and foundational movements as well. Restoring joint function and/or mobility should also be a focus during this time.

The best time to start base training strength is one month after the final race of the previous season. Mobility and foundational movements can be implemented soon after the season, but the mental break is important to consider. So, taking a few weeks completely off is usually a good idea.

During base training, remember that you’re reintroducing load AND volume. Exercises to include include compound lifts and key unilateral lifts such as single-leg deadlifts and split squats. During this phase, it is ideal to introduce assisted plyos and transition to bodyweight plyos. Other key corrective exercises, such as Copenhagen planks, star side planks, lateral lunges, and curtsy lunges, are also good to include.

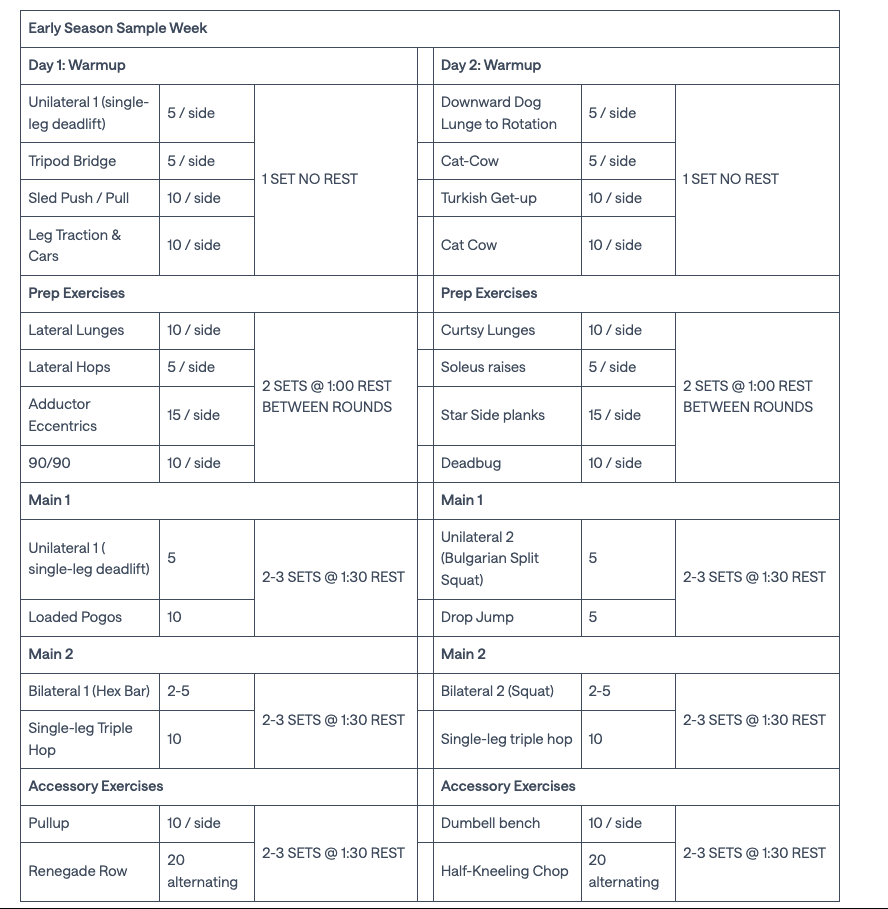

Early Season (8 Weeks)

This phase includes early-season races, and it usually lasts about eight weeks. After six weeks of training, plyos no longer have a delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMs) effect or result in muscular damage. This makes the early season phase a great time to continue building plyos and pairing them with max strength since muscular damage is low. (Keep in mind, though, that central nervous system demand is high.)

As training volume increases, there is going to be a high creatine kinase (CK) production as a result of longer training bouts and an increase in cortisol as well. Plyometrics might have low DOMs and CK production, but top-end strength exercises might make your athlete a little sore. This makes recovery especially important during this phase.

With a strong base built, your athlete is now able to move into a max-strength or power phase. This helps raise your athlete’s strength ceiling and prep for the next phase.

Ideal exercises to include during this phase include hex bar deadlifts, squats, rack pulls, pull-ups, and bench press. Continue with bodyweight plyos, and try to progress to loaded plyos by the end of this phase. It’s also good to continue with key corrective exercises such as Copenhagen planks, star side planks, lateral lunges, and curtsy lunges.

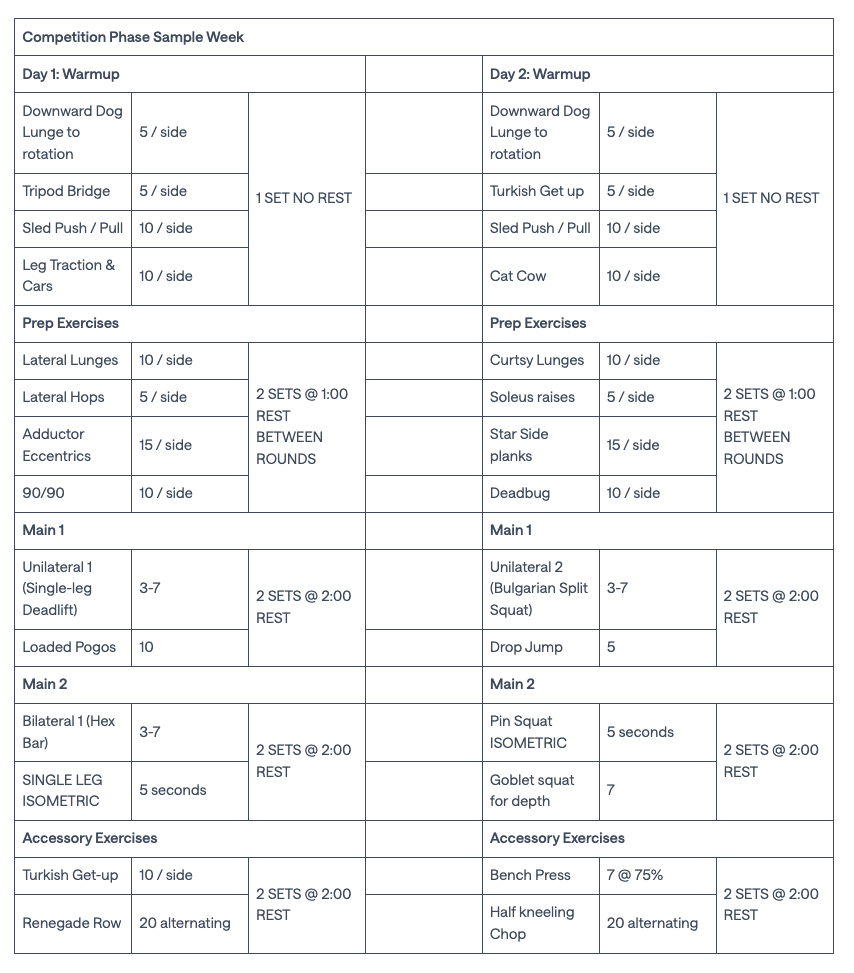

Mid-Season/Competition Phase (16-20+ weeks)

The mid-season competition phase lasts about 16-20+ weeks, depending on the athlete and sport type. Training and racing are the focus during this phase. Volume and intensity will be high with periods of intentional overreaching, so you don’t want strength work to add unnecessary strain to the system. Provided you’ve already trained well in the off- and pre-season, the exercises should not impede training but rather enhance your athlete’s ability to train, race, and recover.

You’re looking to maintain during this phase. The goal is to maintain strength at a level that does not provide increased or new training stimulus. You’re also trying to mitigate injury by focusing on key areas of high use, which depends on your athlete’s sport. For example, a cyclist or marathoner may have tight hip flexors and adductor complexes that limit gluteal function and posture. In this case, you should try to lengthen and eccentrically load the hip flexors and adductors while strengthening gluteal and abduction function.

Include exercises such as the hex bar deadlift and squats. Put a larger emphasis on dynamic movements such as standing lift and chop movements, lateral lunges, and plyos. Plyometrics should be maintained. During high-volume or intensity weeks of training, replace load with isometrics at 90% effort.

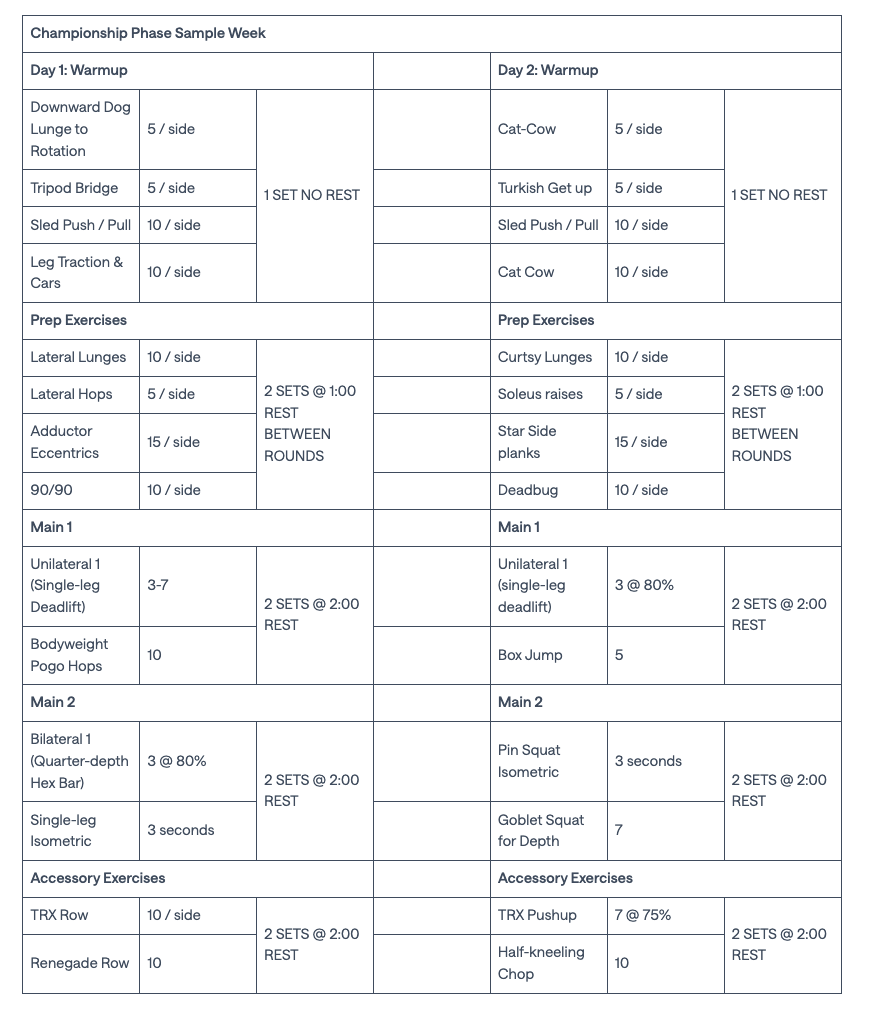

Championship Phase (4-6 weeks)

This phase includes the big races at the end of the season. The championship season is often a big variable as many things are changing or in flux. The athlete has gone through a long season of training, so mental and physical fatigue is high. The goal during this phase is to maintain strength with the minimal effective dose, mitigate injury, and modify sessions according to the athlete’s schedule and needs. Maintain, mitigate, and modify. That’s it.

Include a reduced range of motion squats and deadlifts during this phase, and reduce both volume and load. During high-volume or intensity weeks, replace load with isometrics at 80% effort. Put larger emphasis on bodyweight or light-load, full range-of-motion exercises such as slider lunges or deep goblet squats.

Remember, a great strength program is tailored to the individual and includes movements specific to that athlete. It should address individual weaknesses, build sport-specific muscles, prevent injury, and be modified throughout the season. When programmed correctly, strength training allows endurance athletes to excel and reach levels within their sport.

References

Beattie, K., Kenny, I.C., Lyons, M. et al. (2014, February 15). The Effect of Strength Training on Performance in Endurance Athletes. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0157-y

Brearley, S., Wild, J., Agar-Newman, D., & Cizmic, H. (2017). How to monitor net plyometric stress: guidelines for the coach. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324755442_How_to_monitor_net_plyometric_stress_guidelines_for_the_coach

Durall, C., & Sawhney, R. (2006). Chapter 4 – Strength. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B072164077X500255

Hoff, J., Gran, A., & Helgerud J. (2002, October). Maximal strength training improves aerobic endurance performance. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12383074/

Jamurtas, A., et al. (2000, February). Effects of Plyometric Exercise on Muscle Soreness and Plasma Creatine Kinase Levels and Its Comparison with Eccentric and Concentric Exercise. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/2000/02000/Effects_of_Plyometric_Exercise_on_Muscle_Soreness.12.aspx

Isner-Horobeti, M., et al. (2013). Eccentric Exercise Training: Modalities, Applications and Perspectives. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0052-y

Mikkola, J., et al. (2007, May). Concurrent endurance and explosive type strength training increases activation and fast force production of leg extensor muscles in endurance athletes. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17530970/

Robineau, J., et al. (2016, March). Specific Training Effects of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Exercises Depend on Recovery Duration. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25546450/

Rønnestad, B.R., & Mujika, I. (2013, August 5). Optimizing strength training for running and cycling endurance performance: A review. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sms.12104

Siegel A., Silverman, L., & Lopez, R. (1980, July). Creatine kinase elevations in marathon runners: relationship to training and competition. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2595821/