As technology continues to change how we communicate and train, athletes have access to an unprecedented number of motivating and demotivating factors. Social media, instantaneous coach feedback, and various new platforms for performance and competition have all changed the landscape of sports, along with athletes’ reasons for doing them. Motivation is defined on a global level as the direction and intensity of effort (Sage, 1977), and no matter the platform, it’s essential to an athlete’s perceived reason and self-determination. Therefore it needs to be both understood and balanced for success in sport.

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

According to self-determination theory, motivation has essentially two sources: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic motivation comes in the form of rewards, which are generally provided by other people in the form of negative or positive reinforcement. These rewards may be comprised of praise, constraints, awards, money—and now with the growing presence of social media, things like likes, comments, and virtual KOM/QOM’s. Friends, family, coaches, and social followers—even fellow participants/opponents in VR applications—can be considered sources of this extrinsic motivation.

On the other hand, people who are intrinsically motivated endeavor inwardly to be competent and self-determined; especially, in regard to their pursuit to master a given task. Intrinsically motivated athletes participate for the love of the sport, may enjoy competition, focus of having fun, and are excited to learn skills which improve performance (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). It may seem clear which type of athlete you want to be in order to enjoy success and longevity in your sport, but the reality is that most athletes fall somewhere on the motivation spectrum between intrinsic and extrinsic—and their position can change as they experience different stimuli.

The Continuum of Motivation

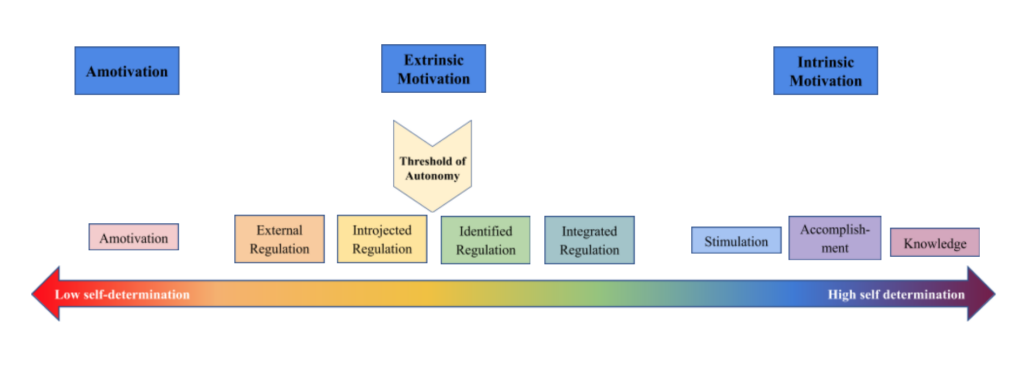

Figure 1.1 shows the multidimensional continuum of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. As we can see, amotivation (or non-motivation) is the lowest form of motivation, leading to pervasive feelings of incompetence and lack of control. Knowledge and high self determination, on the other hand, represent the highest form of motivation.

Extrinsic Motivation

In Figure 1.1 we see external, introjected, identified, and integrated regulation as the four types of extrinsic motivation. This is where many developing athletes may find themselves as they define what their sport means to them. Here are some definitions for each category of external motivation:

External regulation

An athlete’s behavior is controlled by only external sources such as rewards and punishment. For example, a coach uses punishment whenever a workout is missed or executed poorly.

Introjected Regulation

An athlete’s motivation is based on internal impetuses and pressures; their behavior is not self-determined due to the regulation of external factors. For example, an athlete might feel unwell, but chooses to continue with an interval workout because of internal pressure, like posting her/his training on social media. In this case, the audience acts as an external influence on the behavior of the athlete.

Identified Regulation

An athlete’s behavior is accepted, valued, and judged by the athlete themselves. Their actions are performed willingly even if perceived unpleasant. For example, an athlete participates in a sport based on their belief that it will foster individual growth and development.

Integrated Regulation

An athlete participates in the sport due to valued outcomes. While they are still not participating solely for the sake of the sport itself, integrated regulation is the most developed type of extrinsic motivation. Athletes may feel that they’re acting on their free will when external rewards are present. For example, an athlete prepares for an outcome goal (result) at a competition.

Note the threshold of autonomy, which divides this range of extrinsic motivation. This threshold can be considered the vertex that allocates low self-determination and high self-determination on the continuum. Self-determination constructively increases as an athlete becomes more intrinsically motivated, and all types of motivation to the right of the threshold of autonomy result in a feeling of “want” rather than “ought” (Weinberg & Gould, 2015), in relation to training and racing.

Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation is the uppermost form of motivation leading to high self-determination. When an athlete reflects on themselves and considers themselves as cause of their behavior, then the athlete is intrinsically motivated (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). Figure 1.1 shows the three types of intrinsic motivation: stimulation, accomplishment, and knowledge, which can be defined as follows:

Stimulation

The reasons for participating in activities and sports are grounded on pleasant sensations such as excitement, fun, and aesthetics. For example, an athlete engages in an activity or sport to experience aesthetic pleasure of being outside.

Accomplishment

The feeling of mastery creates pleasure and satisfaction in an athlete. Performance and process-oriented goals directed towards the individual and not the outcome (i.e. results) are the keys to feeling accomplished. For example, running a marathon under three hours and eventually achieving it.

Knowledge

An athlete is involved in an activity for the pleasure and satisfaction of learning, exploring, or trying something new. On many occasions, this is the most central impetus of people joining a sport or even switching between disciplines such as from road cycling to gravel riding. However, learning a new skill within a sport can be a great motivator as well.

The Three Components of Intrinsic Motivation

Self-determination theory also suggests that three human needs—competence, autonomy, and relatedness—help cultivate intrinsic motivation. In the realm of athletics, these three components may be defined as follows, and can be creatively extended by coaches and athletes as needed.

Competence

Having a sense of mastery related to one’s own performance and feeling confident and self-efficacious; are factors that impact the feeling of competence. Focusing on process and performance goals related to oneself, and less on outcome goals such as results; this, potentially fosters an individual’s motivation.

Autonomy

An athlete should have a say in the decision making of a given training plan; incorporating workouts that convey a sense of independence; for example, choosing the intensity, duration, equipment, schedule et cetera. Furthermore, coaches should listen to requests of their athletes and design the training regime accordingly.

Relatedness

Engaging in a group or community of individuals with the same interests such as a network of athletic peers, care for others, and to have them care for the respective person, are examples which may strengthen the sense of relatedness.

These three important elements significantly shape an individual’s intrinsic motivation and every coach should be aware of the nature of these dynamics (Weinberg & Gould, 2015).

What if You’re Extrinsically Motivated?

Of course, the various types of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation are not exclusive. Self-determination is multidimensional, and most athletes will experience a blend of several types of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation throughout their careers. Neither is wrong; extrinsic and intrinsic motivation go hand in hand in the realm of performance sports. The question merely is to which extent an athlete tends.

Highly successful athletes, for example, tend to be more intrinsically motivated by setting themselves as a standard of excellence and focusing on individual improvement rather than outcomes. However, outcome goals are still important for these athletes in order to progress their skills. Downplaying ego-orientation (opponents, competitive goal, et cetera) and concentrating on the tasks on hand will lead to a satisfactory equilibrium and higher self-determination.

A Note On Social Media and Motivation

Most would agree that openly sharing workouts on social media, riding in virtual competitions, or going for QOM/KOM can be assigned to the extrinsic spectrum; especially, in the context of knowingly performing in front of an audience. Nowadays, it easy to build a follower base of hundreds of people, potentially imposing a feeling of “being watched” on the athlete. This may affect athletic or performance-oriented motivation on a global level, due to getting rewarded more frequently (or not) by atypical extrinsic rewards such as large amounts of comments, likes, et cetera.

Many athlete-oriented social platforms have rightfully recognized the issue and introduced process-oriented monitoring options and performance-oriented goals or challenges. Athletes also have the option of keeping workouts private to focus on their process and performance.

On the other hand, some VR applications (especially in cycling) offer users the opportunity to participate in competitions almost 24 hours a day, seven days a week. When athletes can compete against others from all over the planet; to gain extrinsic rewards, it’s up to them to understand how this affects their motivation, and whether it’s helping them reach their goals.

Athletic motives may have changed over the past two decades towards a generally more extrinsically focused environment. With so many possible extrinsic rewards conveyed by technology, it can be difficult for athletes to develop their own intrinsic motivation. Chasing extrinsic rewards rather than intrinsic ones does not create enduring commitments, and reduces the feeling of achievement (Kohn, 1993).

Fortunately, like with most things in life, the antidote is to have find a balance. Find the right dose of each type of motivation, and you’ll establish a productive equilibrium. This is especially true in the realm of athletics. Certainly, technologies such as VR/AR and social media can be great tools to stimulate an athlete’s motivation, but as the dose of extrinsic motivation becomes too high, feelings of achievement and task-oriented mastery might be sacrificed. To rekindle excitement and satisfaction in sports, athletes should aim for a balance of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

References

Kohn, A. (1993). Why incentive plans cannot work.

Sage, G. (1977). Introduction to motor behavior: A neuropsychological approach (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2015). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology (6th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.