At the elite level of running, 40 really is the new 30. Everywhere you look, elite runners old enough to compete as masters are kicking but in open competition. For example, on September 21, 2014, American Deena Kastor, age 41, took third place in the Philadelphia Rock ‘n’ Roll Half Marathon with a time of 1:09:36. A month earlier, Great Britain’s Joanne Pavey won the European Championships 10,000 meters at the age of 40 years, 325 days. Five months before that, Kenyan-born American Bernard Lagat won a silver medal in the indoor world championships 3000 meters just eight months before his 40th birthday. And less than a year before that, Ethiopian legend Haile Gebrselassie, age 40, won the Vienna Half Marathon in 1:01:14.

What Has Changed?

Middle-age runners were not performing at such a high level a generation ago- so what has changed? It is certainly not the case that humans are aging more slowly. The aging process is encoded into our genes, and our genes have not changed much in the last 25 years. Instead of slower aging, I attribute the rising performance level of elite masters runners to these three factors:

- Athletes are taking better care of their bodies throughout their careers

- Expectations about what is possible after turning 40 are changing

- Older runners are benefitting from innovative training methods

It is the last of these factors that I would like to discuss in this three-part series of articles. As an endurance sports journalist, I have quizzed many older elite runners (including Kastor and Gebrselassie) about how they have altered their training methods to accommodate the changing needs and limitations of their bodies so that they can continue to perform at the highest level possible. Through this research I have discovered that one of the more commonly used methods is the extended microcycle.

Extending Your Microcycle

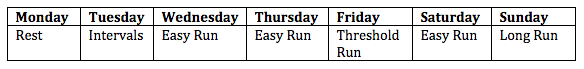

A microcycle is the shortest recurring pattern of training. Most runners use a default seven-day microcycle that looks something like this:

Seven-day microcycles work well for most runners, but they are not ideal for many masters runners. The reason is that runners over 40 don’t recover as quickly from intense or long workouts. The traditional seven-day microcycle packs three “hard” runs into seven days. In the example above, the hard runs are Tuesday’s interval session, Friday’s threshold run, and Sunday’s long run. That’s a bit too much stress in too little time for the typical masters runner.

Advantages of a 9 Day Microcycle

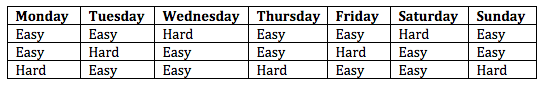

I favor a nine-day microcycle for masters runners. It has a few advantages. One is that it offers a neat-and-tidy routine of two “easy” days following each “hard” day. In experimenting on myself (I’m 43) and in working with other athletes I’ve found that the body settles into a nice, progressive rhythm on this steady routine. You get to know just how hard to go on hard days and how easy to take it on easy days to keep your fitness moving forward.

Another advantage of a nine-day microcycle is that seven repetitions of the hard-easy-easy triad adds up to 21 days, or three weeks. So you don’t have to completely abandon the convenience of lining up your training with the standard seven-day week in the process of embracing extended microcycles. The only downside of this schedule is that long runs don’t always fall on the weekend, instead landing on Friday in the second week of every three-week block. But runners should not do a really long run every single week anyway, so I typically schedule a shorter long run on that Friday and it works out just fine.

Below is a generic example of a 21-day block of training with nine-day microcycles. Note that “easy” days may be rest days or may feature an easy run, a fartlek run, or a fast-finish run, while “hard days” may feature an interval run, a threshold run, or a long run.

One more advantage of this pattern is that it dovetails nicely with another method that successful masters runners use to stay fast after 40: block periodization. I will discuss block periodization and how it fits together with nine-day microcycles in Part 2 of this series.

Other Methods

Extending the microcycle is not the only way runners over 40 can accommodate their reduced rate of recovery. Alternatively, they can retain a seven-day microcycle and just do easier hard runs (e.g. fewer intervals, shorter long runs). This approach does solve the problem of applying too much stress in too little time, but it does so at the cost of fitness. You can’t get equal fitness from easier workouts. Most runners over 40 find that they can still handle very challenging workouts, just not as often, so there’s no need to make this concession. Retaining the hard workouts and extending the microcycle is the better way to go.

As runners age, turning to alternative training methods can help you retain fitness and avoid injury. By extending the microcycle to 9 days you can balance your hard and easy days to avoid injury and stay fit.