How well different types of drinks are retained in the body is a question I get a fair bit, and it’s of some practical use. In theory, the longer you can keep the fluids you drink onboard the greater the chance they have of being absorbed into the bloodstream and used effectively in the body. There’s also the side benefit of less interruptions for bathroom breaks, which is useful during training and competing.

Whilst you’re inevitably going to pee out a good proportion of all the liquid that passes your lips, all drinks are definitely not treated equally by the body in this particular regard. Substances like caffeine and alcohol have the potential to increase urine output and reduce fluid retention, whilst calories and electrolytes in drinks can slow the emptying rate of the stomach and positively influence the absorption of fluid from the gut into the bloodstream.

Most of the factors affecting how your body processes various drinks have been studied pretty extensively. However, until very recently no one had actually put a range of different, commonly consumed beverages into a controlled ‘head to head’ situation to compare their potential to hydrate. Earlier this year, a respected group of UK scientists published a paper that compared the hydrating potential of the following drinks1.

- Water

- Sparkling water

- Beer (lager)

- Orange Juice

- Coffee

- Tea

- Skimmed and full fat milk

- Oral Rehydration Solution

- Sports drink

- Cola and Diet cola

How the Study Was Conducted

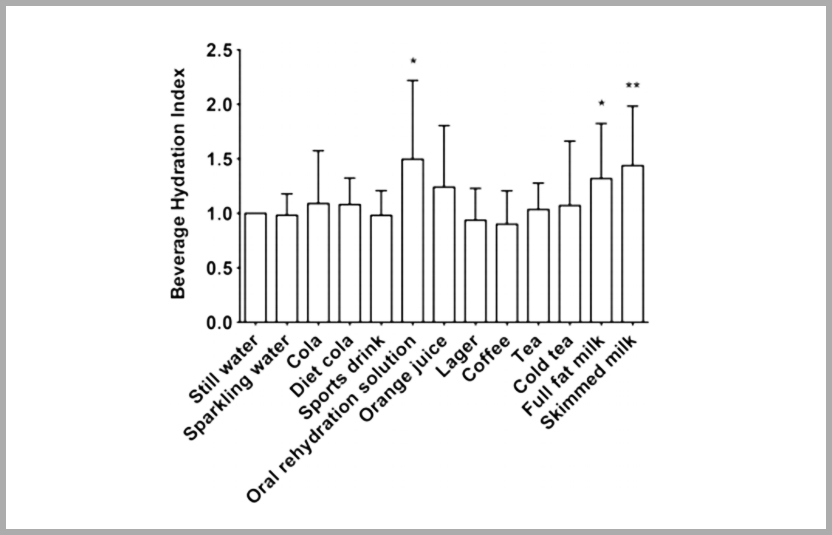

The study compared how well each of the drinks were retained in the two to four hours immediately after consumption. Volunteers downed one litre of fluid and then had their urine output monitored to indicate how much had been retained. Then, to create a straightforward comparison of the drinks, each beverage was given a BHI (Beverage Hydration Index) score. Still water was used as the reference point in the scale with a rating of 1. So, if a drink ended up with a BHI of 1.3 it would mean that 30 percent more of it was retained in the body two hours after consumption than when drinking the same amount of water and so on.

What the Results Showed

There were a few interesting conclusions that came out of the data. Here are four insights that stood out for me.

- At the risk of starting with the seemingly obvious, there wasn’t a difference between the hydrating effect of still or sparkling water. I’m pointing this out simply because I do get asked that question quite often. Though, why anyone would drink fizzy drinks during exercise is beyond me.

- The top performers in terms of fluid retention were ORS, milk, and orange juice. These were the only drinks to perform significantly better than water, with ORS and milk approaching a 1.5 BHI score, meaning 50 percent more fluid was retained in the body two hours after consumption when compared with water alone. The likely reason for this is that they lowered urine output due to the significant amounts of calories and/or electrolytes they contain. That’s especially in the case of ORS, as it has over 1300mg sodium per litre as well as some glucose. Constituents like sugars, fats, and electrolytes have long been known to increase the retention of fluids in the body, but this data highlights just how significantly that’s the case.

- On the flip side, drinks that you might have thought would perform a lot worse than water, such as coffee and lager, actually didn’t result in all that much more urine output than the equivalent volumes of water. Lager even outperformed coffee, perhaps due to its higher calorific content slowing the transit time through the stomach. It’s important to note that the amount of alcohol and caffeine taken in via beer and coffee during the study was actually pretty low. Increasing the intake of these substances might have led to a different conclusion over a longer period of time.

- One other possibly surprising finding was that standard sports drinks were not shown to be much better in terms of fluid retention than plain water. That said, the particular sports drink selected was relatively low in electrolytes, containing only around 450mg/l of sodium and six percent carbohydrate. These amounts are lower in sugar than orange juice and only contain about a third of the electrolytes of ORS, both of which ended up with significantly higher BHI scores. That’s one reason I recommend products with large amounts of electrolytes, up to 1500mg/l,for preloading before a big event. The extra sodium helps you retain more of the fluid you take in for longer.

Practical Advice

Whilst most of the findings of this study are essentially in line with ‘common knowledge’, the data does reinforce and quantify the anecdotal evidence in this area. It also helps to dispel some myths about certain drinks being dehydrating, at least when they’re consumed in moderation. For myself, the main take home points are:

- Drinks with a large calorific content like milk (and by logical extension, recovery shakes) can probably help with rehydration more than you might imagine. They can therefore be extremely useful after strenuous, sweaty exercise when consuming both calories and fluids to assist with recovery is beneficial. This doesn’t necessarily make them great pre-exercise choices though, as you may well not want something highly calorific before training or racing if you’re already getting enough energy from food.

- Solutions very high in sodium, around 1000mg to 1500mg, are also likely to be significantly better than plain water when it comes to retention. So, they’re more appropriate choices both before and after strenuous exercise, when sweat losses are very high and where pre or rehydrating can assist performance or recovery. This is often overlooked pre-race, when many endurance athletes suck down loads of additional water only to end up dropping most of it off in a porta potty before the race even gets underway.

- Whilst some drinks commonly assumed to be dehydrating, like coffee and beer, are clearly not the best choices for hydration purposes, they are actually not significantly less effective than water when consumed in moderate amounts. This should at least take the edge off some of the guilt associated with enjoying a cold beer after a race.

What the Paper Doesn’t Tell Us

Something that the paper perhaps doesn’t shed much light on is the impact of how consuming certain foods and drinks together might affect fluid retention and urine output. It’s rare that we take on fluids in isolation and on an empty stomach, as was the case in the study.

It doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to reach the conclusion that taking in some calories and/or salts in food alongside water is likely to result in increased retention of fluid when compared with drinking fluids alone. To be fair to the researchers, they were seeking to control as many variables as possible to look solely at the properties of each of the drinks. Introducing the interactions of food and fluid together would have made things extremely complicated.

This study clears up some misinformation and gives you real science behind how different fluids affect your body. Now you can make more informed decisions about what you drink before, during, and after training and racing to optimize your performance.