Estimating your sweat rate can be a useful exercise when you’re trying to figure out how much and what you need to drink (in terms of fluids and electrolytes) during training and events. But sweat rate varies considerably from person to person and can also vary quite a lot for any given individual: Things like how hard you’re working, the ambient temperature and humidity, your clothing choices, genetics and heat acclimation status all play a role in determining how fast and how much your body perspires.

Sweat rate measurement is something that should ideally be done on a number of occasions and in a range of conditions if you want the results to help you in specific contexts, like planning your hydration needs for an upcoming race. Here’s a guide for collecting the data you need to get a reasonably accurate idea of your sweat rate. And then some ideas for what to do with the data once you have it.

Equipment You’ll Need to Calculate Your Sweat Rate

- An accurate set of weighing scales

- A dry towel

- Possibly a small, accurate kitchen scale to weigh your water bottles (if you’re planning to drink during the sessions while you’re measuring your sweat rate).

How to Calculate Sweat Rate

Adapted from Asker Jeukendrup’s excellent mysportscience.com

1. Go for a pee and then record your body weight, ideally with no clothes on (that’s A).

2. Perform your session (or event) and record exactly how much you drank. This is easy if you drink from a single bottle or two; simply weigh your bottles before you ride (that’s X) and after (that’s Y) and record the difference (that’s Z). 1 gram = 1 milliliter.*

*Make sure all units are in kg or liters

3. After exercise, towel yourself dry and then record your weight (that’s B). Again, it is best not to wear clothes, as they will hold some sweat.

4. Now subtract your post-exercise weight (B) from your pre-exercise weight (A) to get the weight you lost during the session.

Weight lost (C) = A-B

5. Also subtract the weight of the bottle(s) before (X) and after (Y) to obtain the amount you consumed (Z).

Volume consumed (Z) = X-Y

6. You can now calculate your sweat rate…

(C+Z) / time.

Note: It’s best not to pee during these sessions, as this can skew the results. However, if you do have to go, it’s not a bad estimate to assume a fluid loss of ~0.3l (300ml) per bathroom stop. You then just need to subtract 300ml (0.3kg) from your estimated sweat rate at the end.

I’d generally recommend trying to limit data collection to sessions lasting ~45 minutes to 2 hours. Anything shorter than that can be prone to errors in the equation, and anything longer can start to be skewed by things like fuel utilization (you inevitably burn glycogen during exercise, and this can affect your body weight results).

To make analysis really easy, you can collect all of the data into this spreadsheet along with some relevant notes about your session (mode of exercise, duration in minutes, rough intensity and temperature, whether it was outside or inside etc). The sheet will then spit out a % bodyweight loss figure for that workout and also an estimate of your sweat rate expressed in liters per hour. You can record numerous sessions in the sheet to help you get a handle on what kind of sweat losses you see for different sports, in different weather conditions and at different intensities.

If you test enough, you’ll become very good at ‘guesstimating’ your sweat rate in the future, a dinner party trick of dubious value, if nothing else! Plus, if you’ve also had a sweat test (to find out your sweat sodium concentration—i.e. how much sodium you lose in your sweat— you can add that data in and it will estimate your hourly and total sodium loss numbers too.

Is My Sweat Rate Normal?

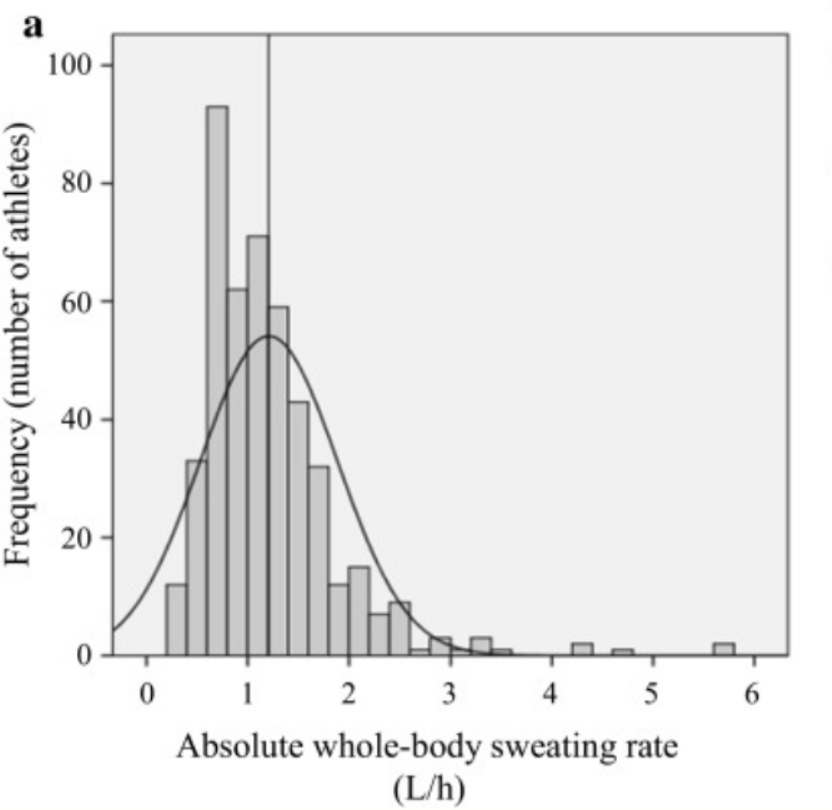

What constitutes a low, moderate or high sweat rate can be tricky, as there are a lot of variables involved. One recent study helpfully looked at a range of sweat rate data collected in a variety of sports. The graph below shows something of a trend in the data from ~500 athletes:

The range of sweat rates in the data was about 0.5 liters per hour to just over 2.5L/hr (save for a few major outliers up at 4-6L/hr!), very similar to the numbers we’ve seen at Precision Hydration in the testing we’ve done with athletes over the years. Another study done at the 2003 Hawaii IRONMAN in Kona also came up with a very similar range of sweat rates.

Based on this data and experience, as a rule of thumb, I’d be inclined to say that anything around 1-1.5L/hr is a ‘normal’/moderate sweat rate (for a healthy adult) during prolonged exercise of a reasonable intensity. Anything much less than 1L/hr would be on the low side, and anything above 2L/hr should be considered high. If you’re losing over 2.5L/hr, then you definitely have a very high sweat rate.

While we’ve seen very high sweat rates (upwards of 3L/hr) in a handful of athletes, it tends to be in very, very big guys (men do tend to have higher sweat rates than women) and/or those working incredibly hard in oppressively hot and humid conditions.

Also, bear in mind that body weight and size factor into all this to a degree, so if you’re a very, very tiny female distance runner but you’re sweating at 1.5L/hr, that might be considered a high or even very high sweat rate for you personally. On the flip side, the same number might be deemed quite low for a 6ft 11in, 330-pound offensive lineman in the NFL. But I’m sure you get the general idea.

What to Do (and Not Do) With the Data

Once you’ve collected a reasonable amount of sweat rate data, the obvious question is: What can you do with the numbers? Again, the answer is not as straightforward as most of us would like it to be.

Many athletes, for example, will find that they sweat at a rate of 1L/hr when running hard and extrapolate that they need to drink 1L/hr when running (i.e., to replace 100% of their losses). There’s a nice simplicity to the concept of ‘1 out = 1 in,’ and for a long time, it was assumed that 100% sweat loss replacement during exercise was likely to deliver an optimal performance. However, time and research have actually shown that hydration is far more complex.

For one thing, 100% replacement often requires drinking beyond the body’s natural thirst instincts, which can be very dangerous. It carries the risk of hyponatremia (low blood sodium levels resulting in some nasty symptoms), and this alone is enough to strongly discourage 100 percent fluid replacement as the ideal. So, what percentage of your losses should you aim to replace?

The answer might be quite a bit lower than you think. You can actually tolerate quite a bit of dehydration (as defined by body weight loss) during training and competition—assuming you start well-hydrated. The exact amount is highly individual and most likely varies a bit day-to-day as well. This blog on how much dehydration you can tolerate is well worth a read to help you understand how much fluid you might want to replace.

It’s also not productive to try to use sweat rate data to try to create a pre-determined, inflexible strategy for fluid and electrolyte replacement. Instead, measuring your sweat rate should be about getting a decent ‘ballpark’ figure for how much sweat (and sodium if you know your sweat composition) you’ll likely lose over a period of time, at a certain intensity and in a particular set of environmental conditions.

If you need help with putting together a hydration plan to test in training, take our free online Sweat Test. If you take it after getting some sweat rate data you’ll be well on your way to answering all your questions on sweat rate with more confidence and accuracy.

References

Baker, L. (2017, March 22). Sweating Rate and Sweat Sodium Concentration in Athletes: A Review of Methodology and Intra/Interindividual Variability. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5371639/

Blow, A. How much dehydration can you tolerate before your performance suffers? Retrieved from https://www.precisionhydration.com/performance-advice/hydration/how-much-dehydration-can-you-tolerate-before-your-performance-suffers/