USAT Level 2 and Elite TrainingBible Coach Jim Vance looks back on five years of data in TrainingPeaks to pinpoint just how much run volume you need to race your fastest Ironman.

There’s an athlete I have worked with for 5 years, and in the time we worked together he went from an 11+ hour Ironman to a PR of 8:59, two podium finishes and multiple qualifications for Kona. He set a new goal in 2013 – to podium at Kona. After assessing the success we’ve had, I began brainstorming about where to go next with his training so that we could achieve this goal.

In order to do this, I had to really go back and examine what we had done in our past Ironman preparations, how we might tweak and change things to get the next breakthrough we’re looking for, and particularly what type of training he responds to best. I had an idea in my mind of what we’ve actually done, and I have his old Performance Management Charts, but I needed to dive in a little deeper and see the bigger picture of how his performances have corresponded with different run training volumes in the past.

Of course, specificity of the run training matters more in the weeks preceding race day, rather than the volume of miles run. I can safely say that each of the 12 weeks leading into the races for this athlete was mostly specific to Ironman. So if the training was specific in its intensity and designed adaptation, then the type of training is consistent and isn’t going to skew the data interpretation. But if the athlete can handle “more” specific training stress, wouldn’t that make him fitter and better? We can look to the data for the answer.

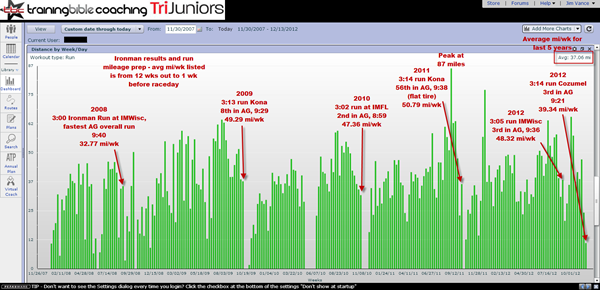

Here’s this athlete’s Distance by Week chart from TrainingPeaks, showing his weekly run volume for the past 5 years.

I pulled this chart to help me see how much run volume helped or hindered his race day performance, and if I should prescribe more volume. It also showed me that I have certain tendencies as a coach, and that perhaps I need to try something different – that might enable the breakthrough we’re looking for.

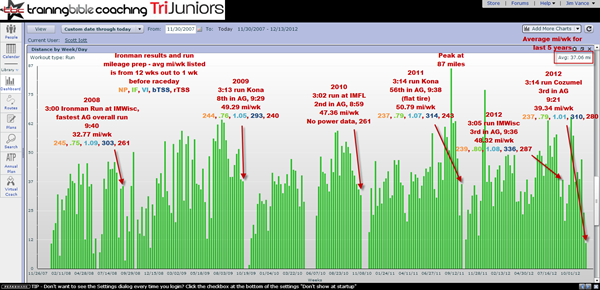

Of course, this volume chart doesn’t show execution or heat/conditions from the races, which probably had more effect than necessarily judging the performance strictly by run split time. So I dug further, and started looking at the execution on race day, with bike statistics like Normalized Power (NP), Intensity Factor (IF), Variability Index (VI), Training Stress Score (TSS) and how these stats all corresponded with run performance (quantified by rTSS in this case). I overlaid these race day stats onto the volume chart:

Before we get started with the analysis on this, let’s define some of the items above:

- NP = Normalized Power from the race

- IF = Intensity factor of the ride, (NP/FTP)

- VI = Variability Index, (how well paced was the ride, steady = 1.00 or close, big variance = 1.05+)

- bTSS = Bike Training Stress Score, the stress the bike put on the athlete, a faster/harder bike will have 300+

- rTSS = Run Training Stress Score, the faster run should have higher rTSS, as the athlete is able to hold faster pace relative to their threshold

As a coach, I looked at these stats to see if there was a mileage that gave us the most benefit? Was there a mileage number which was high, but didn’t provide any more benefit than lower-mileage specific training? Can I pinpoint an optimal number for this athlete, a “bell curve” within which I can keep the mileage range? If so, instead of prescribing more run miles, perhaps I can prescribe more bike or swim volume?

I also noticed that the times this athlete completed his highest mileage have always come in the weeks immediately preceding his Ironman event. What if I manipulated the timing of that volume to come before the “12 week out” mark? Now the athlete comes in strong, and I can lower (or maintain) the volume, but increase intensity. Definitely something I’m considering.

Looking at the chart, some might say he ran great when he was just doing 32 miles a week in 2008, why not go back to that? The main reason is that this was a new stimulus to the athlete back then, and expecting to get the same result is probably not realistic. But certainly it is strong evidence that mileage volume isn’t the biggest determinant of run performance in an Ironman.

“Mileage volume isn’t the biggest determinant of run performance in an Ironman.”

You can see that in 2011, we decided to do the most volume we ever have, thinking that would be a new training stimulus that would give him the breakthrough he needed. You can see that didn’t happen. He flatted in the race, but still, the run was not what we’d hoped.

As some have suggested, running in Wisconsin or Florida is not the same as running in Kona, and the performances may be equitable considering the conditions. This is always something which must be subjectively considered with analysis of the data, how they placed relative to the field, the favorability of the course relative to their strengths or weaknesses, and even the athlete’s mindset.

Considering all of the above, my opinion is that the athlete’s best all-time performance was probably Kona 2009, when he was 8th in his AG against stellar competition and in hot conditions. His next best performance was his 8:59 at IMFL the year after (because of the significance of the 9:00 barrier), and the third best was probably IMWI this year, where he just raced hard and well against a tough field, just missing a top 20 overall finish.

One colleague told me he thought VI on the bike mattered more in Ironman than even IF or TSS, but this athlete’s two highest VI’s corresponded with his fastest and third fastest runs (VI 1.09 and 3:00 run at IMWI in 2008; VI 1.08 and 3:05 run at IMWI 2012). Also bTSS seems to have very little reflection on his run times, as he either runs 3:13-14, or 3-3:05 despite varying bTSS scores. Missing the bike data from Florida 2010 is a bummer, as the unit malfunctioned in the race and thus we have incomplete picture. So is it that this athlete handles courses which require higher VI better than steady state, flat courses? Could be. If so, the Kona bike course with its infamous climb to Hawi and brutal crosswinds could play in his favor.

A lot of information to consider, and as a coach or athlete, reflection on the past is very important if you want to set the right path ahead. The decision I have made with this athlete is to change to the timing of the run volume we do. In general, he will be doing higher run volume in the months leading up to the 12 weeks out from the race, where we will switch to less volume and greater intensity. Is this the right decision? Well, based on the data as evidence, I believe it is. Buy me a coffee at Lava Java in Kona in October after the race, and we can chat about whether I was right or not!

Bottom line is, start using reflection of past data to help drive your training decisions going forward. Talent will get you far, but attention to the details of your training, both current and past, will get you to your potential.