When cycling, especially while racing, we use a mix of aerobic and anaerobic energy to create speed for the day. While sprinting hard to close a gap in a road race or powering up a steep climb on a dirt trail, you’re tapping into both aerobic and anaerobic metabolism to complete the task, but most of the time you’re working aerobically. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate how aerobic and anaerobic the sport of cycling really is, and why it is important for all cycling disciplines to focus on training aerobically the majority of the time.

To begin figuring out how aerobic or anaerobic cycling really is, we first need to learn what all this aerobic and anaerobic stuff means. Aerobic metabolism takes place with the presence of oxygen and anaerobic metabolism happens without the presence of oxygen. So that means sometimes we move, jump or pedal at a certain intensity that requires very little or zero use of oxygen. But the question remains to when and how often this happens while we are riding or racing our bikes?

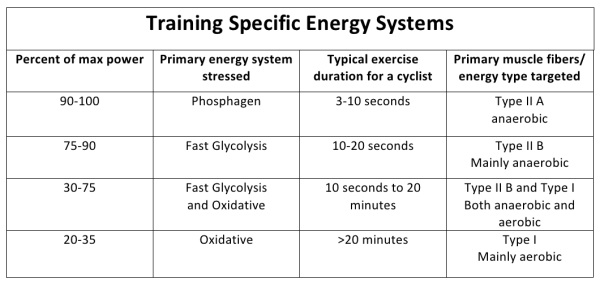

Let’s first learn about physiological energy systems, and begin to look at what is happening on the inside of our bodies while we are training at certain intensities. The chart below is an example of the type of energy system that is targeted at specific intensities1. Peak power charts from a range of abilities, from Category 1 elite to Category 4 cyclists were used to help determine appropriate exercise durations related to percent of max power.

It is important to note that that all energy systems will play a role in most if not all movements at any intensity, but the main focus is on the system that plays the biggest role. As you can see, a true anaerobic action takes place at around 90-100% of your maximum power output, typically lasting between 3-10 seconds. A mix of aerobic and anaerobic energy is used between 30-90% of maximum power and while working under 35% of maximum power output, you are working mainly aerobic systems.

What is interesting is to analyze the ten minutes preceeding the final minute of the race, where Henderson was working near his threshold power ranges, averaging close to 400 watts, to help keep his team near the front of the pack2. When you compare Henderson’s threshold power to his max power output for the day, you can see that even when working hard near his threshold range, he is still only working at 35% of his maximum power ranges. So even though he was working at his threshold power range for a ten minute effort, he was still using a large amount of aerobic energy to complete that task.

The final 3-5 seconds of a sprint to the finish line, where a rider puts as much power into the pedals as possible, is a good example of a cycling effort that is mainly anaerobic. On stage 6 of the 2012 Tour De France, Greg Henderson (Lotto-Belisol) led his teammate Andre Greipel to the finish line, sprinting as his leadout man to give Greipel the best chance for the win. Henderson did a great job that day and Greipel ended up winning the stage. In the last 60 seconds of that race, Henderson produced a max output of 1150 watts (his 2 second Peak Power was 1124 watts, so the max of 1150 watts was most likely for 1 second) and averaged 663 watts2. During that short period of time, especially when he was hammering over the 1000 watt range, Henderson was working mainly anaerobically.

In Part 2 of this article, we are going to analyze the aerobic and anaerobic demands of four different disciplines of cycling. We will use two race files from Greg Henderson and two race files from Jeremiah Bishop to give us a look at both road and off-road cycling races, and determine what that means for the type of training we should be doing.