In part one and part two of this series, we went over the basics of block periodization and how you can strategize the timing of your blocks for specific events. In this article, we will take a look at an actual scenario to give you an idea of what this looks like in practice.

In December of 2019, a cyclocross racer we’ll call MJ came to me. He had just finished his cyclocross season. He was a 45-year old masters racer who had been riding for around 5 years. He was a relative newcomer to the sport compared to other master’s racers who had been racing for decades, but MJ wanted to return the next cyclocross season and compete with the best.

In reviewing his prior training, it was clear that he had the “no pain, no gain” mentality with his training; most of his workouts contained maximal efforts. It was clear that MJ needed to spend some time building his aerobic engine to help support higher intensities needed for cyclocross. Fortunately, we had plenty of time to build up for the 2020 season.

We split the training year into several parts. The spring build-up would implement the block model and focus on his general development rather than preparing for racing. The second build-up would prepare him for the season and focus on race-specificity.

In the initial months, we planned a long accumulation phase. It was winter and MJ lives in the Midwest. He would be spending most of his time on the trainer. This lent itself well to focused interval workouts rather than a long traditional base phase.

Our primary goals in the initial weeks were to build his aerobic engine, strength, and muscular endurance. This is something that he had neglected with his training before, but would set him up well for when the higher intensities would be introduced later.

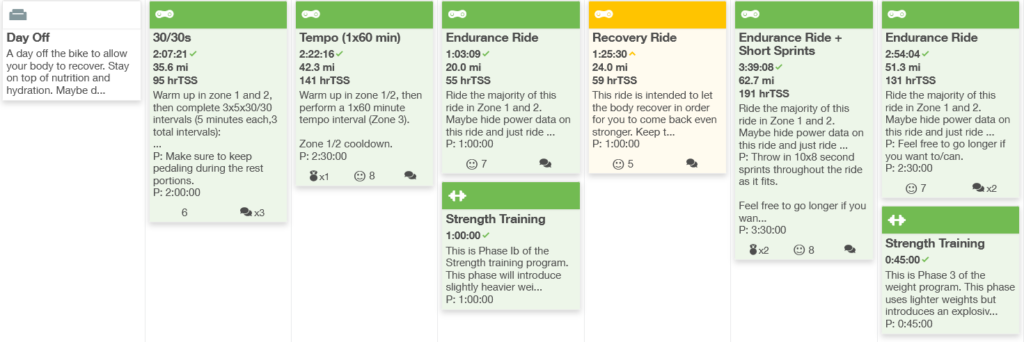

In order to accumulate a large amount of aerobic load with limited training time, we incorporated a lot of tempo, strength intervals, and sprint workouts. The tempo workouts create similar adaptations to longer miles in less time. The strength intervals and sprints would improve neuromuscular recruitment patterns to ensure the gym work was transferring over to the bike.

After the accumulation phase, MJ was ready to enter the transmutation phase. This would take all of the improvements we made in the accumulation phase and translate them over to the higher intensities. The plan with this phase was to focus on aerobic capacity and improve his 5-10 minute power. We started with longer intervals (~8 min) to bank time in the higher zones.

After the first couple weeks of the transmutation block, we then progressed to a to a very focused VO2 block. This would be a very challenging block but would be followed by a restoration phase to allow the body to adapt.

The completion of the spring “development” phase ended in April when the COVID-19 pandemic was in full swing. We decided to approach the season as if it were going to happen, so we would be ready if it went off.

Following the mid-season restoration block, we would begin with a second accumulation block to prepare for the season. The weather was getting nicer and MJ had more time on his hands because of the pandemic. In contrast to the shorter interval workouts as seen in the winter accumulation phase, we would incorporate more volume and longer rides to train his base.

The vast majority of time was spent at endurance pace, but there were some very short higher intensity intervals mixed in just to keep the muscles firing at high power.

MJ’s volume was double that of the winter accumulation phase, but very manageable with lower intensities. Following the second accumulation phase, we focused on improving MJ’s threshold with a focused transmutation block.

When fall came, it was very clear that the season was not going to happen. We took advantage of this time to dial-in the best race approach for MJ and do race simulations. This would help us figure out what would work best for MJ in the next season and help him to work on his cyclocross skills.

During this simulated season, we incorporated shorter blocks than in the winter. This would be very similar to what we would incorporate during an actual season to prepare for important races.

This proved to be very effective and MJ was seeing some major improvements. The typical scheme was an accumulation phase of about 1-2 weeks with tempo workouts and high-volume, followed by a high-intensity race specific transmutation phase and then a rest week.

Each month MJ was seeing quantifiable improvements. The training variation kept things fun and interesting. Fatigue was kept in check and each phase improved performance in the next. The block model was eliciting improvements in all categories.

References

Haff, G.G., & Haff, E.E. (2012). Training Integration and Periodization. In Jay Hoffman (Eds.). NSCA’s Guide to Program Design (pp. 209-254). Location: Human Kinetics.

Issurin, V.B. (2007). A Modern Approach to High-Performance Training: the Block Composition Concept. In: Blumenstein, B. et al. Psychology of Sport Training. Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport. p. 216-34.

Issurin, V.B. (2010, March 1). New Horizons for the Methodology and Physiology of Training Periodization. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20199119/

Sjøgaard, G. (1984, October). Muscle morphology and metabolic potential in elite road cyclists during a season. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6500791/

Verkhoshansky, Y.V. Theory and methodology of sport preparation: block training system for top-level athletes. Teoria i Practica Physicheskoj Culturi, 2007; 4:2-14.