If you’re training for an endurance goal, whether it’s finishing a marathon or completing an IRONMAN, chances are you probably follow some form of structured training. This training likely includes different training zones, intensities, and workouts spread throughout the week.

Every training zone serves a purpose. However, the most effective training plans prioritize Zone 2. This is arguably one of the most important aspects of endurance sports performance.

Many novice or young athletes fall into the trap of thinking the only way to get faster is to always train fast. Unfortunately, this causes them to miss out on performance gains by neglecting Zone 2.

Zone 2 training enhances your athletic performance at the cellular level. It boosts your capacity to use fat efficiently and clear lactate effectively, helping you train longer and build strength. Here’s how.

What is Zone 2 Training

Zone 2 training is steady, low-to-moderate intensity aerobic exercise that builds endurance with minimal fatigue. For most endurance athletes, Zone 2 is approximately 60–70% of max heart rate (or an “all-day” effort you can sustain for a long time without burning out).

Zone 2 is effective because it improves the core systems behind long-distance performance, including mitochondrial function, fat oxidation, and lactate clearance. In practical terms, it helps you go farther, recover faster, and hold stronger pace or power as workouts and races get longer.

What Zone 2 Should Feel Like

- Breathing is controlled and rhythmic

- You can speak in full sentences (the talk test)

- Effort feels “comfortably steady,” not hard or strained

At this intensity, your body can supply enough oxygen to meet energy demands, allowing you to train longer while accumulating relatively low stress—making Zone 2 the foundation of most endurance training plans.

Benefits of Zone 2 Training

Zone 2 training builds your aerobic base with relatively low fatigue, making it one of the most efficient ways to improve endurance performance over time.

- Improves aerobic endurance: Helps you hold steady pace or power longer with less effort.

- Boosts fat burning: Trains your body to use more fat for fuel, saving glycogen for harder efforts and late-race surges.

- Increases mitochondrial function: Builds the cellular “energy engines” that support long-distance performance.

- Enhances lactate clearance: Improves your ability to manage lactate so moderate-to-hard efforts feel more sustainable.

- Supports consistency: Creates meaningful adaptation without the recovery cost of constant high-intensity training.

Pro Athletes Don’t Skip Zone 2 Training (And Neither Should You)

I have worked with professional and elite endurance athletes for more than 18 years, including cyclists, runners, triathletes, swimmers, and rowers. During this time, I’ve come to understand that Zone 2 training is paramount to improving performance.

Elite endurance athletes dedicate between 60-75% of their entire training time in Zone 2.

Very similar data across many different sports has been described by coaches worldwide, as well as in the scientific literature.

The purpose of each training zone is to elicit specific physiological and metabolic adaptations. Understanding what physiological and metabolic adaptations occur at different intensities can help you fine-tune and improve your training.

To know this, you first need to understand the science behind how it works.

How Zone 2 Training Works: The Physiology of Endurance

To understand why “going slow makes you fast,” you must look at how your body produces energy at the cellular level.

1. Muscle Fiber Recruitment

Skeletal muscle consists of two kinds of muscle fibers — Type I, also known as slow twitch, and Type II, fast twitch.

Fast twitch fibers are also divided into two subgroups called Type IIa and IIb. Muscle fiber contraction follows a sequential recruitment pattern where Type I muscle fibers are recruited first.

As exercise intensity increases, muscle contractile demands increase, and Type I muscle fibers can’t sustain the demand. This is when Type IIa muscle fibers kick in, and eventually, as intensity keeps increasing, Type IIb are finally recruited.

Simply put, slow twitch fibers are used at slower speeds and fast twitch at faster speeds.

Each muscle fiber has different biochemical properties and, thus, different behaviors during exercise and competition.

- Type I (Slow-Twitch): Recruited during Zone 2. These fibers have the highest mitochondrial density and are designed for aerobic efficiency.

- Type II (Fast-Twitch): Recruited during high-intensity intervals (Zones 4-5). These rely on anaerobic glycolysis and produce higher levels of lactate.

You stimulate Type I muscle fibers during Zone 2 training. Therefore, you stimulate mitochondrial growth and function, which improves your ability to utilize fat. This is key to performance for endurance athletes.

By improving your body’s ability to utilize fat as fuel, you preserve glycogen. You can then use that glycogen at the end of the race or workout when intensity increases.

2. Fat vs. Carbohydrate Utilization

The majority of exercise intensities generate ATP through aerobic metabolism, also called oxidative phosphorylation. Depending on the fitness level of an individual, ATP synthesis (energy) is generated from fat and carbohydrates, although carbs are used at small rates during low and moderate exercise intensities.

At higher exercise intensities (beyond 75% of VO2 max), ATP generation increases to maintain muscle contractile demands.

Fat cannot synthesize ATP fast enough, so carbohydrate utilization increases and becomes the predominant energy substrate. This is because energy synthesis derived from carbs is faster than fat.

Carbohydrates becomes the main energy substrate skeletal muscles use at exercise intensities up to 100% of VO2max. Beyond this intensity, ATP cannot be generated by aerobic glycolysis, so ATP needs to be generated through the anaerobic mechanism, also called substrate phosphorylation.

Essentially, going slowly lets your body use fats as fuel, and as you increase the pace, you increase the demand for carbohydrates.

| Training Zone | Intensity | Primary Muscle Fiber | Primary Fuel Source |

| Zone 1 | Very Low | Type I (Slow) | Fat |

| Zone 2 | Moderate | Type I (Slow) | Fat (Max Oxidation) |

| Zone 3 | Tempo | Type I & IIa | Mix of Fat/Carbs |

| Zone 4 | Threshold | Type IIa (Fast) | Carbohydrates |

| Zone 5 | Anaerobic | Type IIb (Fast) | ATP / Glucose |

3. The Role of Lactate Clearance

The majority of exercise intensities generate ATP through aerobic metabolism, also called oxidative phosphorylation. Depending on the fitness level of an individual, ATP synthesis (energy) is generated from fat and carbohydrates, although carbs are used at small rates during low and moderate exercise intensities.

At higher exercise intensities (beyond 75% of VO2 max), ATP generation increases to maintain muscle contractile demands.

Fat cannot synthesize ATP fast enough, so carbohydrate utilization increases and becomes the predominant energy substrate. This is because energy synthesis derived from carbs is faster than fat.

Carbohydrates becomes the main energy substrate skeletal muscles use at exercise intensities up to 100% of VO2max. Beyond this intensity, ATP cannot be generated by aerobic glycolysis, so ATP needs to be generated through the anaerobic mechanism, also called substrate phosphorylation.

Essentially, going slowly lets your body use fats as fuel, and as you increase the pace, you increase the demand for carbohydrates.

How Do You Know if You’re Training in Zone 2?

Threshold tests are one of the best ways to establish truly personalized training zones. But not every athlete has access to a lab, and even if you do, lab testing isn’t always practical to repeat throughout the season.

The good news is you can still find Zone 2 using at-home methods that are accurate enough to guide day-to-day training. (If you want to go deeper, you can read more about lactate threshold here.)

Here are a few reliable ways to identify Zone 2:

- Lactate testing (if available): If you have access to blood lactate testing, Zone 2 is often the intensity where lactate stays relatively steady, typically around 1.5–2.0 mmol/L for many endurance athletes. This suggests you’re primarily fueling aerobically and can sustain the effort for a long duration without rapidly accumulating fatigue.

- Heart rate: A common guideline for Zone 2 is 60–70% of max heart rate, though this can vary based on fitness, fatigue, heat, hydration, and stress. Use heart rate as a guardrail, but focus on keeping the effort smooth and controlled rather than chasing an exact number every day.

- The talk test: Zone 2 should feel “comfortably steady.” You should be able to speak in full sentences and hold a real conversation without needing frequent pauses for breath. If you can only get out a few words at a time, you’re likely above Zone 2. (Here’s a more in-depth explanation of how to use the talk test: The Importance of Lactate Threshold and How to Find Yours.)

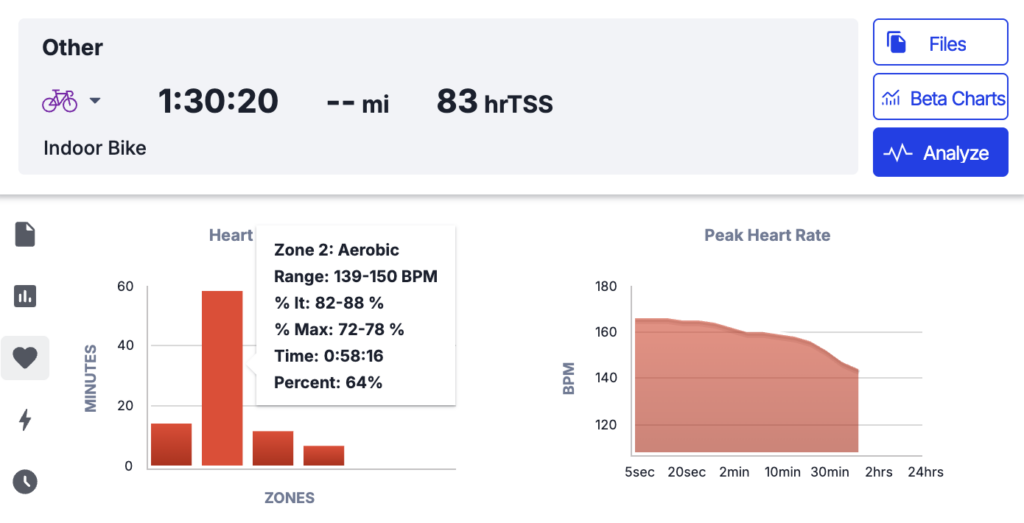

Once you’ve identified Zone 2 for you, use tools like TrainingPeaks’ Time in Zones charts to keep yourself on track—especially on days that are meant to be easy.

Training Tip → Any time you re-test and update your threshold, make sure you also update your zones in TrainingPeaks so your targets and charts stay accurate.

How Often Should You Train in Zone 2?

An endurance athlete should never stop training in Zone 2.

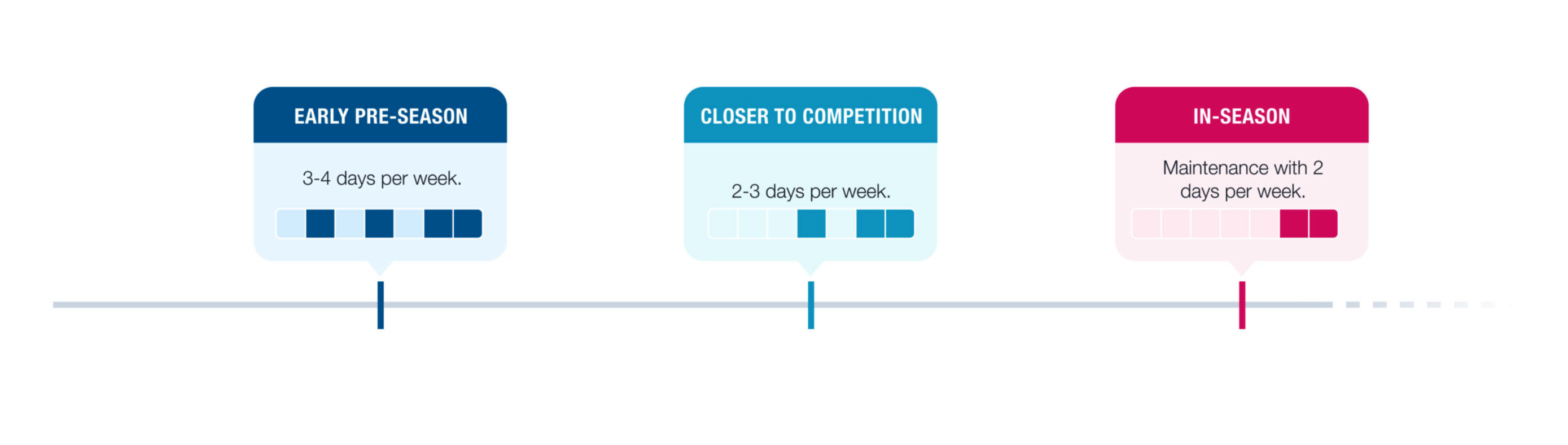

The ideal training plan should include 3-4 days a week of Zone 2 training in the first 2-3 months of pre-season training, followed by 2-3 days a week as the season gets closer and two days of maintenance once the season is in full swing.

For most endurance athletes, the ideal frequency depends on the season:

- Base Phase (Pre-season): 3–4 sessions per week.

- Build Phase: 2–3 sessions per week.

- Race Season: 2 sessions per week for maintenance.

Incorporating regular Zone 2 training into your routine not only boosts your endurance and fat utilization but also enhances your overall performance, making it an essential component for athletes at any level.

Learn more about Zone 2 researching and how pro athletes are using it, check out this CoachCast: Zone 2 Biochemistry for Biomechanical Energy with Iñigo San Millán.