When launched, WKO4 introduced the Power Duration Model, a robust construct of the power duration relationship for cyclists designed by Dr. Andrew Coggan. This model is the foundation of a number of analytical tools in WKO4 and allows for the tracking of new training metrics capable of giving us deeper insight into an athlete’s ability and fitness.

Initially, Power Duration Curve metrics featured Pmax, Functional Reserve Capacity (FRC), and modeled Functional Threshold Power (mFTP). These allowed tracking of sprint power, anaerobic work capacity, and threshold power. In the most recent feature release of WKO4, Dr. Coggan has introduced the new tracking metric of stamina to assist coaches and athletes in tracking the development of fatigue resistance over prolonged efforts. The purpose of this article is to define stamina and describe the basis of this new metric.

Introduction to Stamina

Stamina in endurance sports is the ability (both physically and mentally) to keep performing for a long period of time. All endurance sports require stamina, although some—such as Ironman distance triathlons, marathon running, and long endurance events—require more stamina than others. Developing peak physical condition results in endurance athletes having a high degree of stamina because their hearts, lungs, and muscles all function at a high level of efficiency.

WKO4 Stamina Defined

For use in WKO4, the metric is defined as follows:

Stamina: a measure of resistance to fatigue during prolonged-duration, moderate-intensity (i.e., sub-FTP) exercise. Units are percent of maximum, i.e., 0-100%, although most individuals will fall in the 75 to 85 percent range.

Stamina represents time periods beyond 1 hour of performance, scoring your resistance to fatigue over such longer efforts. On the power duration curve, this is typically the “flat tail” of the extended curve beyond about one hour.

The Basis and Purpose of Stamina in WKO4

Stamina is a power-duration-derived metric that takes into account all points of an athlete’s power data to quantify resistance to fatigue during prolonged exercise. As a simple example, a stamina score of 100 percent would represent complete fatigue resistance, and the power duration curve beyond one hour(ish) would be completely flat, whereas a 50 percent stamina score would show significant decline of the tail. If fatigue is what causes you to slow down, then being more resistance to fatigue means that you won’t have to slow down as soon or as much.

The purpose of the metric is to track and analyze an athlete’s endurance fitness over time in an effort to understand:

- Response to training stimuli in increasing performance in prolonged duration exercise

- Effectiveness of training regime on increasing stamina

- Athlete’s readiness to perform

Physiological Factors Behind Stamina

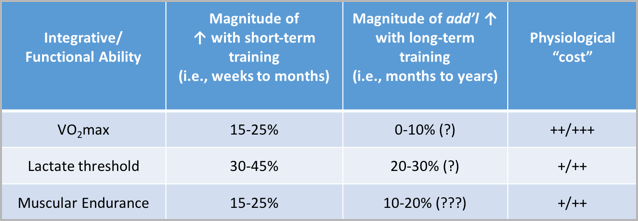

While there are many factors that impact our stamina, the most important is our muscular metabolic fitness. Endurance training induces major adaptations in skeletal muscle. These include increases in the mitochondrial content and respiratory capacity of the muscle fibers. As a consequence of the increase in mitochondria, exercise of the same intensity produces less metabolic strain than in untrained muscles. Additionally, endurance training has consistently shown a fast-to-slow conversion in response to such training. That is, highly-fatigable fast-twitch type IIX fibers are converted into the more fatigue-resistant type IIA fibers, and some type IIA fibers may even be converted into the slower contracting, less powerful, but highly fatigue-resistant type slow twitch type I fibers. The major metabolic results of these adaptations are a slower utilization of muscle glycogen and blood glucose, a greater reliance on fat oxidation, and less lactate production during exercise of a given intensity. These adaptations therefore play an important role in the large increase of the ability to perform prolonged strenuous exercise that occurs in response to endurance exercise training.

The adaptations described above result in an increase in functional threshold power (FTP), which is the highest exercise intensity at which aerobic ATP production balances ATP demand, such that a steady-state (or quasi-steady-state) of physiological responses (e.g., blood lactate levels) can be maintained. If cardiovascular fitness, i.e., VO2Max, sets the upper limit for aerobic exercise, it is one’s muscular metabolic fitness, as reflected by FTP, that determines how much of that aerobic upper limit can be used. Thus, FTP and stamina are closely related, with the former describing the level at which the power-duration relationship tends to plateau and the latter describing the rate of decline once past that point in time. Even with the same FTP, however, there can be subtle differences between individuals in stamina, depending in part on genetically-influenced fiber type distribution, training specificity, habitual diet, etc.

Building Stamina in the Endurance Athlete

Stamina is a metric that assigns a score to a specific adaptation to training stimuli (or lack thereof). As stamina increases, one could expect an improvement in longer, steady-state endurance events such as triathlons, endurance cycling, and even marathons. Understanding the basis of stamina as described in this article gives us insight into the types of training that can best increase it.

Progress Training Duration

Whatever your present endurance conditioning, build it slowly but steadily to begin to increase your stamina. This increase in duration needs to occur at two levels: first, in total training duration, and second, in the length and pace of your longer rides.

Overall duration increase is the simplest way to increase your base fitness and increase stamina (assuming it occurs in the appropriate training zones). The strategy of increasing total training duration at a steady 10 percent per week has been around for a long time for a reason: it is a smart way to build stamina. It’s important to note that just building time should not be the focus; building time at the appropriate effort is imperative to success. As duration increases the athlete should ensure the progression of time in Zone 2, Zone 3, and Sweet Spot to maximize aerobic conditioning and base.

Extending individual ride duration is a highly effective way to not only increase overall duration but also specifically develop stamina by mimicking the stress of longer endurance events. This means extending at least one ride (two is better) a week to a longer duration based on your target events. To further improve stamina results, these rides should be completed in Zone 2 and Zone 3 efforts.

Focus on Building Functioning Threshold Power

Physiologically, FTP is most related to stamina. The introduction of at least 3 to 5 workouts per training macrocycle (2 to 5 weeks) focused specifically on raising threshold performance will pay dividends in the development of stamina. These workouts should focus on training intensities in the Coggan iLevels’ Zone 4a, also known as Sweet Spot Training. This allows an athlete to push threshold up from below, increasing such threshold while still focusing on aerobic efforts.

Build Aerobic Capacity

As noted, increasing aerobic capacity is measured by VO2Max. Some training focus should be placed on workouts that maintain and build this capacity in the endurance athlete. With the new iLevels, athletes can maximize results by completing specific intervals in the Coggan iLevel Zones 5 and 6. These intervals should be completed when fresh so the athlete can get maximal effort and time in the training zones. Add 2 to 4 of these style of workouts per training cycling to best maximize results.

Stamina is an effective metric for tracking the increase (or decrease) in fatigue resistance to prolonged efforts. This puts another tool in the coach or athletes hands to better track the effectiveness of training strategies and predict performance results.

Dr. Andrew Coggan contributed to this article.

Download a free 14 day trial of WKO4