In part one of this series, we discussed the limitations of the traditional sequenced model of periodization and how you can use a more advanced model, block periodization, to benefit your training. It is highly recommended that you read part one before reading part two.

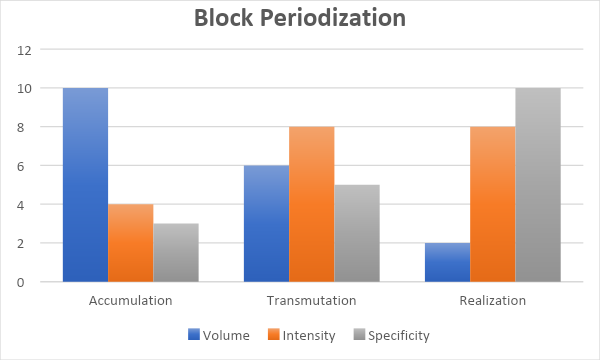

There are three main phases in block periodization: Accumulation, Transmutation, and Realization. It’s great to know what these phases are, but the timing of each is critical for best results. Within each phase, the volume, intensity, and event-specificity is varied. The figure below summarizes the areas of focus for each phase within a block:

Timing of Block Periodization Training

Each phase operates on the notion that the current phase will improve performance in the next. For example, by improving my oxidative capacity in an accumulation phase, I will have a higher level of performance when beginning a high-intensity transmutation phase.

Understanding the concept of residuals is critical to implementing block periodization. Since each training phase is highly focused on a handful of abilities, other abilities are naturally forgone. Timing each block so that all abilities are at optimal levels leading up to competition is crucial.

If you have too long of a gap in between your accumulation phase and competition, for example, your aerobic “base” and endurance might not be at a sufficient level. Conversely, if you end your transmutation phase too late, the trained energy systems might not have enough time to regenerate to their highest level before competition. See the diagram below for a visual.

As you can see, the training done in the accumulation phase has the longest residual, in that this ability can be maintained the longest leading up to competition. This training also takes the longest to develop, and naturally should be your longest phase.

The higher intensity transmutation phase does not take as much time to train, but it is lost much quicker. It also creates a higher risk of overtraining. This phase should be shorter and be done close to competition. With this design, high-intensity adaptations are at optimal levels but fatigue is less because of the shorter duration in the transmutation phase.

The restoration phase length depends on the type of athlete and the event. A short, intense event will require a longer restoration phase. A race of this nature demands that the body is fully rested to perform optimally. A longer event will require a shorter taper. Some athletes will perform better with longer or shorter rest periods and this must also be considered.

The best timing for your blocks depends on the event and the time of year. If you have 3 or 4 “A” events in the year, naturally your blocks can be a little longer. If you want to perform at a high level for every event, the blocks will be shorter. In general, the more important the event the longer your blocks should be.

Another thing to keep in mind is that the longer time you spend in a phase, the longer the residual will last. If you have multiple events of equal importance back-to-back, a longer block prior to the events is necessary to create residuals that will last through the racing period.

Block Periodization: Event-Specific Recommendations

For longer endurance type events (Ironman, marathons, etc.) the accumulation phase should be on the longer side (~4 weeks). This of course depends on the time in between big events as a longer block may not be feasible. The accumulation phase represents the most important phase since the large workload needed for these events is critical.

The transmutation and restoration phases should be short. This will ensure that the endurance is maintained but also provide time for the athlete to fine tune the engine and recover ahead of competition. After tapering for these types of events, athletes often feel “stale” heading in, causing an elevated submaximal HR and poor sensations. A shorter transmutation and restoration phase will usually solve this problem because the residuals from the accumulation block will still be running strong.

For shorter events (criteriums, short road races, 5k races etc..) the accumulation phase might not need to be as long, and a greater amount of time should be spent in the transmutation block. This will ensure the athlete has accumulated enough time in the high-intensity zones to perform and will not be overcooked from an arduous accumulation phase. The rest period prior to the event should be longer as well. Short events require a great deal of freshness to find peak performance.

It’s important to make a plan for your training blocks before heading into the season. Make note of your most important events. Then, think about what the primary demands of these events are, this will allow you to determine how much time you need to spend in each phase. With block periodization, it is possible to find multiple peaks throughout the year. Small blocks as short as 4 weeks can give you a proper lead up to a mid-season goal.

Block Periodization: Training Recommendations

Block periodization is not only for race preparation but is also a great training tool during the offseason or for those who do not race but just want to improve. If you are seeking to improve as an athlete, change your primary focus within each block and continually increase the workloads. This training variation will continually overload your body and allow you to reach new heights. If you want to improve at a certain aspect of competition, that should naturally be your primary focus within each block.

In practice, block periodization can be hard to visualize. What does this actually look like for an athlete? In the next part of this series, we will take a look at an athlete who has used block periodization to find a new level of fitness.

References

Haff, G.G., & Haff, E.E. (2012). Training Integration and Periodization. In Jay Hoffman (Eds.). NSCA’s Guide to Program Design (pp. 209-254). Location: Human Kinetics.

Issurin, V.B. (2007). A Modern Approach to High-Performance Training: the Block Composition Concept. In: Blumenstein, B. et al. Psychology of Sport Training. Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport. p. 216-34.

Issurin, V.B. (2010, March 1). New Horizons for the Methodology and Physiology of Training Periodization. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20199119/