Put simply, if you want to run fast—then you need to run fast, often. Old school coaches used to reserve speed work for the weeks immediately leading up to their athletes’ main races, but now all the top pros advocate speedwork much earlier in the season for a variety of reasons.

However, speedwork, especially in the early season, is often dreaded by the endurance-focused athlete. Usually the athlete has built a base of endurance and retained most of it during the holiday season, so they are reluctant to cut the mileage down so they can up the pace. Why should they begin speed work now? Well a (gentle) shock to the system is your signal that race season is only a few short months away, which can be a good thing. Keep doing what you’ve been doing the past three months and you’ll just become more of a one speed engine.

If you commit to getting faster now, say over the next six weeks, you’ll increase your endurance speed for same effort, or possibly even run at faster endurance speeds more economically by spring.

It’s important to remember that you don’t always need access to a track for dedicated V02 max or above-threshold sessions. A fartlek incorporating speed work using road signs, different colored cars or distance timers on your watch all help to maintain motivation in a fun way away from the track. Benefits to early season speedwork are many, not counting the physiological advantages. When combined with early season targeted core work, the difference in run posture is noticeable, not to mention the injury prevention so critical to a multisport athlete.

Form and technique also benefit as shorter distances, coupled with adequate recovery, enable you to run mindfully, fully engaged, and, if with club mates or friends—a little bit competitively. Slogging around a long run on your own during the early season in the Northern Hemisphere is not always fun, no matter how effective your layering, and the extended time causes the mind to wander, and with it your run form. Speedwork generally improves your form, you can focus on making sure your footfall is under the hips, that you’re landing flat or on the ball of the foot (it’s hard to heel strike running fast), and your cadence and posture improve as well.

We have great fun asking athletes to run to specific paces during these sessions because most athletes simply run too fast and cannot stay consistent. Learning what running fast feels like can aid your race strategy, so that you are not tempted to run another athlete’s race but execute the pace you know you can maintain come race day. It’s great practice for those tough races where speed is needed to qualify or overtake a rival in the finish chute.

Timing of speedwork sessions are key; usually our athletes do their threshold bike training earlier in the week, leaving the weekend for the longer, slower efforts, however, this means that fitting in a run speed session or two can be tricky to avoid arriving at a higher intensity session tired and below par. It is for this reason that we very often focus separately on speed work, having a revolving run, bike and swim block, never trying for speedwork in all three disciplines simultaneously.

With our athletes at Lovetri, we use a series of fun track or speed-related sessions, depending upon the athlete, their goals and their abilities. For marathon runners, speedwork might look like “Yasso 800’s,” where your goal marathon time in hours and minutes is translated to minutes and seconds and applied to a series of 800-meter intervals.

For Sprint-distance athletes and novices, we sometimes use an easily replicable-anywhere speed interval set that an athlete can see improvement in over a number of weeks. We’ll then increase the number of intervals as they get faster and fitter.

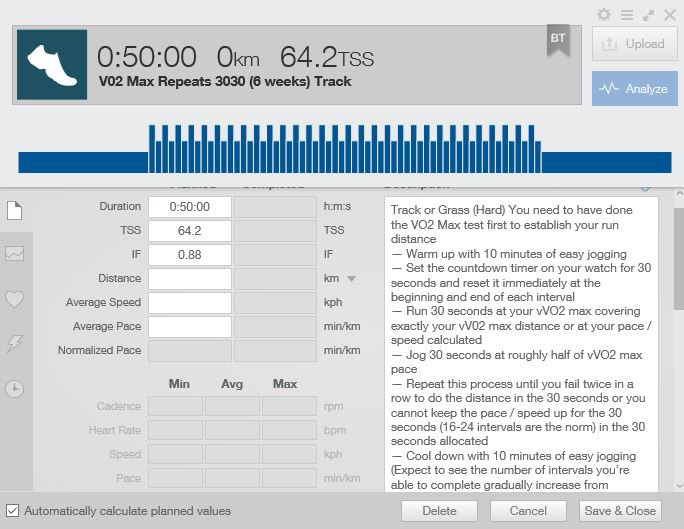

We ask them to run a six-minute time trial on a track or flat bit of road, then divide the total distance they ran by 12 to get the distance covered per 30 seconds. So, for example suppose an athlete runs 1,720 meters in their six-minute time trial. One 12th of this distance is 143 meters. In their speedwork sessions that’s the distance they must cover every 30 seconds until their form falls away or they fail to complete the distance twice in a row. As they get fitter the distances and times increase (if they’re not moved onto a different speedwork session within that period of time).

For those more technically minded, we have them perform the Cooper 12-minute test, readily findable online, to ascertain their V02 max speed. Then we apply those speeds to a range of speed work or interval sessions over different distances within their season, goals and race distances.

What is key of course, in all these early season sessions, is a decent pre-race activation session for 15 minutes or so, focusing on warming up the main muscle groups (including the brain!). The clue here is running-fast specificity, so hamstring stretches are out, and donkey kicks, hip hikes, monster walks and other track drills are in. This is followed post-session with a selection of your main warm down series of stretches. A tip to make you do this series of dynamic exercises: Always carry a small card with you with them written down because when you’ve bothered to write it down and bring with, you’ll do them and not be tempted to run cold (which is a fast-track to injury).

Finally have fun, play a bit, and remember that your speed work is just that, not someone else’s pacing. And it’s also not racing, it’s just ensuring that you have that extra bit in the tank when you need it.

Stay tuned for part 2 of our early season speed series where we’ll look at how to incorporate speed into your early season bike training and for part 3, which will focus on swim speed.